Tania Pardo

Curator, researcher and Director of Museo CA2M.

‘ A Reflection Based on Origin and Form’

Contribution to the catalogue of the exhibition Cristina Garrido. The Origin of Forms. Ed. Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M (2024).

In 1981, the artist Sophie Calle asks her mother to contact a detective agency and commission them to spy on her relentlessly for a day. The result would be condensed into a series of notes and photographs titled The Detective that chronicle the artist’s daily actions in Paris. Calle’s interest in autobiography was a way to explore notions such as intimacy and the construction of identity, as reflected in the many works throughout her career that appertain to life stories. But Calle is not alone in drawing upon her own life in order to create artwork; many other artists have opened up and shared their private lives, addressing issues that relate to even the most intimate aspects. Such is the case of Tracey Emin’s iconic tent, made in 1995, on which the artist showed the names of all the people she had ever slept with, though not necessarily for sex. This piece, along with My Bed (1998), exemplifies and takes to an extreme the notion of turning one’s own biography into art, as Emin herself recounts in the book Strangeland, published in 2005. In essence, self-referentiality has meant not only letting spectators into artists’ lives but also inviting them to get to know their families and bear witness to the ensuing relationships. The most notorious example of this is the series of photographs that Richard Billingham dedicated to the story of his family, in which the protagonists—a chronic-alcoholic father, a disorientated brother, and a chainsmoking mother—take us into a plot of sordid British social reality. Accompanied with texts by the artist on some of the situations shown in the photographs, as a way of enhancing the visual impact of the narration, these images were compiled and published in 1996 as Ray’s a Laugh, which years later was made into a film.

These very issues—the construction of the self and the relationship with one’s parents—are precisely the focus of Cristina Garrido’sm latest work, The Origin of Forms. Although the artist’s previous work has centered on the inner workings of contemporary art systems, each of her proposals is based on a different aspect of the systems of representation that make up the art world. To that end, Garrido appropriates images and supports, be they installations, magazine interventions, museum postcards, performances, photographs, or videos, which she tackles through diverse strategies, seeking to address the different players in the industry. In this particular project—created specifically for the Museo CA2M and arising from the exhibition The Best Job in the World (Fundación DIDAC, Santiago de Compostela, 2021), an investigation into the figure of artists who abandon their practice1—Garrido traces new forms of inquiry grounded on her own biography. But let’s take it one step at a time. In Garrido’s previous project, she held conversations with a number of Spanish creators who had been active in the domestic art circuit between the 1980s and the 2000s, focusing on the reasons why they ended up abandoning art as a profession. From that moment on, she started asking herself about the factors that determine whether artists continue or abandon their practice, and what kind of considerations have a bearing on their remaining within the art system. She then opted to place herself in the center of the research, looking into her background as a way to refl ect upon what factors play a role in this continuation or abandonment of art, and the extent to which an artist’s life story is decisive with regards to the development of what we understand as their talent, vocation, or success.

In this way, The Origin of Forms reflects—through Garrido’s biographical data—on how biography can be used as a tool of knowledge for investigating the matter of how and why artists remain, or not, in the fi eld of art. From there, it invites reflection on some of the terms often used to defi ne the context of the art world, thereby generating a constellation of vital concepts for its construction. In Garrido’s case, the unconditional support of her parents since she was a child was a decisive factor. Nobody in her family had contacts in the art world, nor had any of them ever worked in an artistic profession. However, Garrido’s family encouraged her to study and train in the fi ne arts. Another decisive occurrence was that, after inheriting some money, her father decided to buy a forty-square-meter basement in Madrid’s Chamberí district, so that Cristina could use it as a studio in the future. These premises became her refuge and the space where she developed her work in the first decade of her career. Furthermore, having this property meant that she could live off the sales of her works and devote herself completely to different paid activities related to art, such as giving talks, putting on exhibitions, or running workshops.

In sum, Garrido’s project uses the biographical approach to construct a qualitative research methodology that incorporates the artist’s background, while also considering information that is left out of official accounts and taking on board anecdotal information as part of the construction of her narrative. Let us concentrate on some of the objects that form part of this installation, namely the traces of Cristina Garrido’s memories of her family and childhood, which run throughout the show. One such object is a charcoal portrait of her paternal grandfather drawn by a great-uncle of hers; she always found this drawing somewhat troubling since her grandfather —himself the son of an unknown father—hardly shared any information about his own life. Displayed alongside this portrait are two large maps of Algiers and Venice that were colored in by Garrido’s maternal grandfather, Luis, a draftsman in a mine in Mieres, Asturias, who enjoyed coloring maps as a hobby. There are also two paintings by her father and mother, respectively, which demonstrate the artistic sensibility of them both: we see here the keen interest of two people, two amateur painters from outside the art world, who want to reflect their admiration for Auguste Renoir. Both amateur copyists thus become part of the exhibition, helping piece together the setting in which the artist spent her childhood. For Garrido, the objects, figures, and images that she grew up with played a determining role in her practice and, over time, have served to shore up her own artistic development.

![]() Installation view of the exhibition Cristina Garrido. El origen de las formas. Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M (Móstoles, 2023). Image: Roberto Ruiz.

Installation view of the exhibition Cristina Garrido. El origen de las formas. Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M (Móstoles, 2023). Image: Roberto Ruiz.

The exhibit also shows little Cristina happily running around the galleries at the Musée d’Orsay, in what we know was a trip to Paris with her father. He also recorded her drawing, on a hot day, in front of the Eiffel Tower. These images were fi lmed with those typical 1990s VHS video cameras that bore witness to any and all kinds of family events. But, isn’t all of this a clear tribute to the parents of the artist, who asks us how important such family figures are when it comes to forming an artistic identity? If we look at the data provided in the installation Masters of Western Painting (2023), which forms part of this same project, we realize that, as early as the fifteenth century, the figures of the mother and father, as well as encouragement from the family, have long been crucial for shaping the personality and enabling the livelihood of many artists. There are great historical examples, such as the one told by Frida Kahlo, whose father, a photographer, encouraged her to paint after she was injured in a bus crash. Or that of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who spoke on more than one occasion about how his mother’s unconditional support was fundamental to him, as well as about the vital, revelatory experience of seeing Picasso’s Guernica when he visited the MoMA with her when he was just seven years old. Picasso too always spoke of the support of his father, José Ruiz y Blasco, a conventional painter and academic who soon noticed his son’s extraordinary and superior ability. And Salvador Dalí’s father, despite the complicated relationship they had, was always supportive of his son becoming an artist, sending him at a very young age to study at what was then considered the best art school in Spain, the Royal Academy of San Fernando.

Moving on to the other data presented in this installation, the biographies presented by Garrido also feature astrological signs, as a nod to the standardization of statistics, while confronting us with historical realities such as the shortage of women artists throughout history, the supremacy of white privilege, and Western centrality. However, as Lucy R. Lippard notes, “Despite the importance of the statistics that enrage us and spur us to action, for the artists themselves—that is, those of ‘color’, those from ‘other’ cultures (in other words, non-Eurocentric ones) or women and queer artists—the real matter is not about whether they should be invited to participate in more themed or ‘special’ exhibitions (without denying the fact that, historically, such shows have been effective). Quite simply, what they want, when exhibitions are being organized, is to be included in the group of respectable artists worth taking into consideration.”2

Garrido’s installation features one hundred biographies in an ironic use of data-based methodology. Starting with each artist’s name, date and place of birth and death, race, and astrological sign, they are practically documentary reviews, reminding us how problematic this approach is and the many questions that remain pending for future historiography. In each of them, we come across ideas that have perpetuated the particular way of understanding and consuming art history, such as “the magical aura surrounding the representational arts and their creators [that] has, of course, given birth to myths since the earliest times.”3 Ever since her first works, Cristina Garrido has examined different aspects of the art system with a scrutinizing and objective gaze. Among other matters, she has sought to analyze the symbolism of the erasure of the artistic object (Velo de invisibilidad [Veil of Invisibility], 2011); market trends (#JWIITMTESDSA? Just what is it that makes today’s exhibitions so different, so appealing?, 2015-2017); the staging of the commercialization of art (Best Booths, 2017); the confrontation of the European pictorial tradition with contemporary art production (El copista [The Copyist], 2018-2019); and how the professional roles in the system have changed (Booth Exhibitions Are the Institutions of Our Time, 2020). And she has done so by deconstructing the canonical discourses of art history, bringing color back to mythical images of black-and-white performance records converted today into art objects (Colored, 2022); or, as noted above, interviewing those who have abandoned the art system and creating an installation with the results (The Best Job in the World, 2021). Garrido’s present project differs from all the previous ones in that, for the fi rst time, she openly draws upon her own life experience to reexamine issues that run throughout all her practice and that could be extrapolated to the whole art community: livelihood, origins, the social conditions within which an artist develops, education, social class, the social codes of the art context . . . In conclusion, all those matters that so many are reluctant to talk about and that are often disregarded as the mere dregs of intrahistories and the anecdotal.

This is, therefore, a project that seeks to focus on analyzing the recognition or success of the artist by taking into account the construction of their identity, via what Pierre Bourdieu defined as the logic of vocation in terms of what we understand as “talent.”

![]() Veil of Invisibility – Untitled (Leg), 2015

Veil of Invisibility – Untitled (Leg), 2015

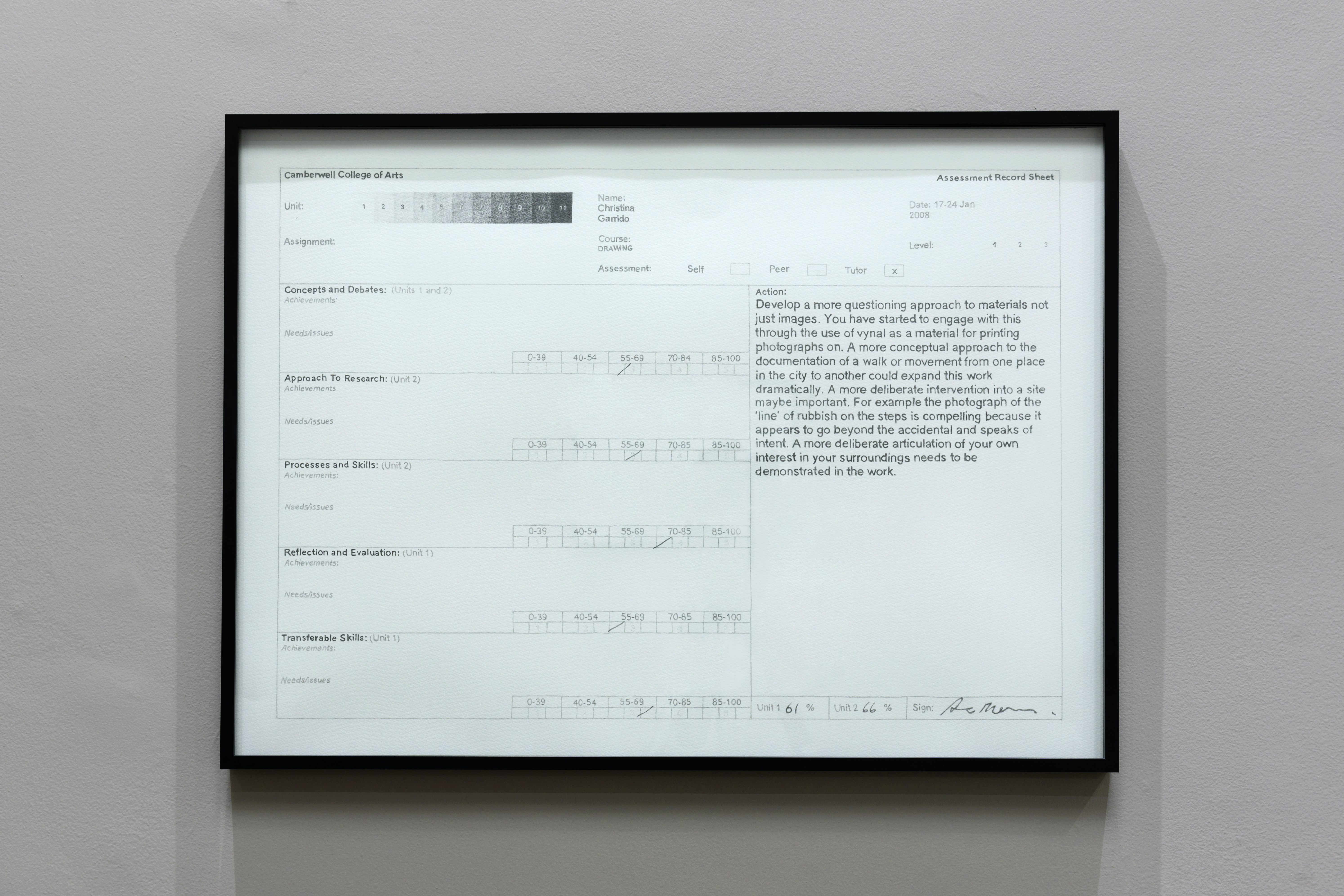

Through the construction of this personal, subjective account, The Origin of Forms makes use of biographical material to create a series of accounts situated somewhere between personal experience and realist fi ction. It is an approach that Garrido had already made use of, timidly, in previous works like The Culture of This Course (2016), where she recovered her tutors’ notes from the year she spent as an Erasmus student at the CamberwellCollege of Arts in London, which analyzed her acquired skills and achievements, mostly in relation to her practice’s scope for conceptualization. This is also the case in TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN (2014), where Garrido transcribed a recommendation letter written by her boss at one of the jobs she held while studying and turned it into a large mural installation. Or, finally, in Clocking In and Out (2015), in which, for a week, every day upon waking up and going to sleep, she posted a selfie of herself online, in a nod to Mladen Stilinovic’s Artist at Work (1978).

The result is an exhibition conceived as an investigation based on life experience and memory, in which Garrido shares a family archive made up of objects and photographs of herself drawing as a child taken by her father—a starting point that turns her life experience and the relationship with her parents into the backbone of the whole proposal. In the face of an endemically patriarchal structure, the canonical narrative of which has expelled numerous women from its center, for many women artists self-referentiality has become a tool for asking questions—within the system itself—about their own inclusion and approach to art as a form of self-affirmation. Eva Hesse dealt with this matter in her writings, in which she indiscriminately wove together the story of her intimate relationship with Tom Doyle, also a sculptor, with the discovery of new material for her work, thus bringing to light her own insecurities within system ruled by male artists. The director of the New Museum, Marcia Tucker, also wrote of her life experience in the book A Short Life of Trouble: Forty Years in the New York Art World, describing her life experience as an indissoluble tool of the art profession. This was along the same lines previously undertaken by Gala Dalí, who revealed herself as an outstanding writer. As Estrella de Diego describes, “If all texts are somewhat autobiographical, a place for negotiating meaning between what is written and what is read, then all life is somewhat fictional. And this is true in the case of Gala, Salvador, and Gala-Salvador Dalí. I still think that autobiography is an extension of fi ction, not the other way round: life is shaped by imagination, more so than by experience.”4

![]() The Culture of this Course (2016)

The Culture of this Course (2016)

The inclusion of the works by her father and mother in Cristina Garrido’s exhibition brings to mind other artists who have collaborated directly with their parents. Such is the case of Hanna Wilke, who used her mother as a model; Selma Butter, who did so to speak of illness and death; Vivian Sutter, who works in collaboration with her mother, the expert collage artist Elisabeth Wild; or Dorothy Iannone, who staged exhibitions in dialogue with the works that her mother made and sent her as gifts throughout her life. Although these are all paradigmatic examples, perhaps the greatest exponent of this idea is Anna Maria Maiolino and her legendary photograph alongside her mother and daughter, which readdresses idea of construction and maternity.

The Origin of Forms features many ideas that, like arrows shot in different directions, speak to us of the contextual causes in the formation of artists, of their individual life circumstances and what these mean in terms of the construction of identity, the formation of the creator, and the development of an art career. However, the project also reveals the degree of randomness involved in all of this, and how seemingly trivial facts and events can and do play a decisive role. The concept of luck—that algorithm that is impossible to control yet so powerful when embarking on a career—is also evoked by Sophie Calle when refl ecting, once again, on the role of chance within the fi eld of artistic creation and, more broadly, in existence and human experience.

* * *

Cristina Garrido. Twentieth and twenty-first century. Spanish. White woman. Leo. Born into a family with no artistic background. Her maternal grandfather, a draftsman in a mine in northern Spain, colors in maps as a hobby. Her father, a great admirer of Renoir, encourages her interest in art from a very young age and takes her to world-renowned museums, visiting Paris’ Musée d’Orsay on several occasions. She studies at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she specializes in painting and drawing. She spends a year studying in London. Back in Madrid, she soon establishes contact with the most relevant artistic circles of her generation. She travels to different countries thanks to residency programs and grants and, before long, begins to participate in art fairs. She shows her first solo exhibition in a national institution when she is barely thirty years old.

1. As Cristina Garrido herself explains with regards to The Best Job in the World: “Although I collected a wide range of very different testimonies—that is, life stories—this search brought to light some highly dissuasive factors that were shared in all cases with regards to the artists’ decision to abandon the art world: most of them found themselves in a position of economic precariousness, were not encouraged by their families to continue their work, and—even those who had achieved certain visibility in the field for a number of years— did not have the necessary contacts to pursue a long-term art career.” Conversation between Cristina Garrido and Tania Pardo, May 14, 2021.

2. Lucy. R. Lippard, “Foreword,” in Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), pp. 6−11.

3. Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” [1971], in Women, Art, and Power (New York: Harper and Row, 1988), p. 153.

4. Estrella de Diego, “Prólogo,” in Gala Dalí, La vida secreta. Diario íntimo (Madrid: Galaxia Gutenberg, 1998), p. 25.

Curator, researcher and Director of Museo CA2M.

‘ A Reflection Based on Origin and Form’

Contribution to the catalogue of the exhibition Cristina Garrido. The Origin of Forms. Ed. Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M (2024).

In 1981, the artist Sophie Calle asks her mother to contact a detective agency and commission them to spy on her relentlessly for a day. The result would be condensed into a series of notes and photographs titled The Detective that chronicle the artist’s daily actions in Paris. Calle’s interest in autobiography was a way to explore notions such as intimacy and the construction of identity, as reflected in the many works throughout her career that appertain to life stories. But Calle is not alone in drawing upon her own life in order to create artwork; many other artists have opened up and shared their private lives, addressing issues that relate to even the most intimate aspects. Such is the case of Tracey Emin’s iconic tent, made in 1995, on which the artist showed the names of all the people she had ever slept with, though not necessarily for sex. This piece, along with My Bed (1998), exemplifies and takes to an extreme the notion of turning one’s own biography into art, as Emin herself recounts in the book Strangeland, published in 2005. In essence, self-referentiality has meant not only letting spectators into artists’ lives but also inviting them to get to know their families and bear witness to the ensuing relationships. The most notorious example of this is the series of photographs that Richard Billingham dedicated to the story of his family, in which the protagonists—a chronic-alcoholic father, a disorientated brother, and a chainsmoking mother—take us into a plot of sordid British social reality. Accompanied with texts by the artist on some of the situations shown in the photographs, as a way of enhancing the visual impact of the narration, these images were compiled and published in 1996 as Ray’s a Laugh, which years later was made into a film.

These very issues—the construction of the self and the relationship with one’s parents—are precisely the focus of Cristina Garrido’sm latest work, The Origin of Forms. Although the artist’s previous work has centered on the inner workings of contemporary art systems, each of her proposals is based on a different aspect of the systems of representation that make up the art world. To that end, Garrido appropriates images and supports, be they installations, magazine interventions, museum postcards, performances, photographs, or videos, which she tackles through diverse strategies, seeking to address the different players in the industry. In this particular project—created specifically for the Museo CA2M and arising from the exhibition The Best Job in the World (Fundación DIDAC, Santiago de Compostela, 2021), an investigation into the figure of artists who abandon their practice1—Garrido traces new forms of inquiry grounded on her own biography. But let’s take it one step at a time. In Garrido’s previous project, she held conversations with a number of Spanish creators who had been active in the domestic art circuit between the 1980s and the 2000s, focusing on the reasons why they ended up abandoning art as a profession. From that moment on, she started asking herself about the factors that determine whether artists continue or abandon their practice, and what kind of considerations have a bearing on their remaining within the art system. She then opted to place herself in the center of the research, looking into her background as a way to refl ect upon what factors play a role in this continuation or abandonment of art, and the extent to which an artist’s life story is decisive with regards to the development of what we understand as their talent, vocation, or success.

In this way, The Origin of Forms reflects—through Garrido’s biographical data—on how biography can be used as a tool of knowledge for investigating the matter of how and why artists remain, or not, in the fi eld of art. From there, it invites reflection on some of the terms often used to defi ne the context of the art world, thereby generating a constellation of vital concepts for its construction. In Garrido’s case, the unconditional support of her parents since she was a child was a decisive factor. Nobody in her family had contacts in the art world, nor had any of them ever worked in an artistic profession. However, Garrido’s family encouraged her to study and train in the fi ne arts. Another decisive occurrence was that, after inheriting some money, her father decided to buy a forty-square-meter basement in Madrid’s Chamberí district, so that Cristina could use it as a studio in the future. These premises became her refuge and the space where she developed her work in the first decade of her career. Furthermore, having this property meant that she could live off the sales of her works and devote herself completely to different paid activities related to art, such as giving talks, putting on exhibitions, or running workshops.

In sum, Garrido’s project uses the biographical approach to construct a qualitative research methodology that incorporates the artist’s background, while also considering information that is left out of official accounts and taking on board anecdotal information as part of the construction of her narrative. Let us concentrate on some of the objects that form part of this installation, namely the traces of Cristina Garrido’s memories of her family and childhood, which run throughout the show. One such object is a charcoal portrait of her paternal grandfather drawn by a great-uncle of hers; she always found this drawing somewhat troubling since her grandfather —himself the son of an unknown father—hardly shared any information about his own life. Displayed alongside this portrait are two large maps of Algiers and Venice that were colored in by Garrido’s maternal grandfather, Luis, a draftsman in a mine in Mieres, Asturias, who enjoyed coloring maps as a hobby. There are also two paintings by her father and mother, respectively, which demonstrate the artistic sensibility of them both: we see here the keen interest of two people, two amateur painters from outside the art world, who want to reflect their admiration for Auguste Renoir. Both amateur copyists thus become part of the exhibition, helping piece together the setting in which the artist spent her childhood. For Garrido, the objects, figures, and images that she grew up with played a determining role in her practice and, over time, have served to shore up her own artistic development.

Installation view of the exhibition Cristina Garrido. El origen de las formas. Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M (Móstoles, 2023). Image: Roberto Ruiz.

Installation view of the exhibition Cristina Garrido. El origen de las formas. Museo Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo - CA2M (Móstoles, 2023). Image: Roberto Ruiz.

The exhibit also shows little Cristina happily running around the galleries at the Musée d’Orsay, in what we know was a trip to Paris with her father. He also recorded her drawing, on a hot day, in front of the Eiffel Tower. These images were fi lmed with those typical 1990s VHS video cameras that bore witness to any and all kinds of family events. But, isn’t all of this a clear tribute to the parents of the artist, who asks us how important such family figures are when it comes to forming an artistic identity? If we look at the data provided in the installation Masters of Western Painting (2023), which forms part of this same project, we realize that, as early as the fifteenth century, the figures of the mother and father, as well as encouragement from the family, have long been crucial for shaping the personality and enabling the livelihood of many artists. There are great historical examples, such as the one told by Frida Kahlo, whose father, a photographer, encouraged her to paint after she was injured in a bus crash. Or that of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who spoke on more than one occasion about how his mother’s unconditional support was fundamental to him, as well as about the vital, revelatory experience of seeing Picasso’s Guernica when he visited the MoMA with her when he was just seven years old. Picasso too always spoke of the support of his father, José Ruiz y Blasco, a conventional painter and academic who soon noticed his son’s extraordinary and superior ability. And Salvador Dalí’s father, despite the complicated relationship they had, was always supportive of his son becoming an artist, sending him at a very young age to study at what was then considered the best art school in Spain, the Royal Academy of San Fernando.

Moving on to the other data presented in this installation, the biographies presented by Garrido also feature astrological signs, as a nod to the standardization of statistics, while confronting us with historical realities such as the shortage of women artists throughout history, the supremacy of white privilege, and Western centrality. However, as Lucy R. Lippard notes, “Despite the importance of the statistics that enrage us and spur us to action, for the artists themselves—that is, those of ‘color’, those from ‘other’ cultures (in other words, non-Eurocentric ones) or women and queer artists—the real matter is not about whether they should be invited to participate in more themed or ‘special’ exhibitions (without denying the fact that, historically, such shows have been effective). Quite simply, what they want, when exhibitions are being organized, is to be included in the group of respectable artists worth taking into consideration.”2

Garrido’s installation features one hundred biographies in an ironic use of data-based methodology. Starting with each artist’s name, date and place of birth and death, race, and astrological sign, they are practically documentary reviews, reminding us how problematic this approach is and the many questions that remain pending for future historiography. In each of them, we come across ideas that have perpetuated the particular way of understanding and consuming art history, such as “the magical aura surrounding the representational arts and their creators [that] has, of course, given birth to myths since the earliest times.”3 Ever since her first works, Cristina Garrido has examined different aspects of the art system with a scrutinizing and objective gaze. Among other matters, she has sought to analyze the symbolism of the erasure of the artistic object (Velo de invisibilidad [Veil of Invisibility], 2011); market trends (#JWIITMTESDSA? Just what is it that makes today’s exhibitions so different, so appealing?, 2015-2017); the staging of the commercialization of art (Best Booths, 2017); the confrontation of the European pictorial tradition with contemporary art production (El copista [The Copyist], 2018-2019); and how the professional roles in the system have changed (Booth Exhibitions Are the Institutions of Our Time, 2020). And she has done so by deconstructing the canonical discourses of art history, bringing color back to mythical images of black-and-white performance records converted today into art objects (Colored, 2022); or, as noted above, interviewing those who have abandoned the art system and creating an installation with the results (The Best Job in the World, 2021). Garrido’s present project differs from all the previous ones in that, for the fi rst time, she openly draws upon her own life experience to reexamine issues that run throughout all her practice and that could be extrapolated to the whole art community: livelihood, origins, the social conditions within which an artist develops, education, social class, the social codes of the art context . . . In conclusion, all those matters that so many are reluctant to talk about and that are often disregarded as the mere dregs of intrahistories and the anecdotal.

This is, therefore, a project that seeks to focus on analyzing the recognition or success of the artist by taking into account the construction of their identity, via what Pierre Bourdieu defined as the logic of vocation in terms of what we understand as “talent.”

Veil of Invisibility – Untitled (Leg), 2015

Veil of Invisibility – Untitled (Leg), 2015

Through the construction of this personal, subjective account, The Origin of Forms makes use of biographical material to create a series of accounts situated somewhere between personal experience and realist fi ction. It is an approach that Garrido had already made use of, timidly, in previous works like The Culture of This Course (2016), where she recovered her tutors’ notes from the year she spent as an Erasmus student at the CamberwellCollege of Arts in London, which analyzed her acquired skills and achievements, mostly in relation to her practice’s scope for conceptualization. This is also the case in TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN (2014), where Garrido transcribed a recommendation letter written by her boss at one of the jobs she held while studying and turned it into a large mural installation. Or, finally, in Clocking In and Out (2015), in which, for a week, every day upon waking up and going to sleep, she posted a selfie of herself online, in a nod to Mladen Stilinovic’s Artist at Work (1978).

The result is an exhibition conceived as an investigation based on life experience and memory, in which Garrido shares a family archive made up of objects and photographs of herself drawing as a child taken by her father—a starting point that turns her life experience and the relationship with her parents into the backbone of the whole proposal. In the face of an endemically patriarchal structure, the canonical narrative of which has expelled numerous women from its center, for many women artists self-referentiality has become a tool for asking questions—within the system itself—about their own inclusion and approach to art as a form of self-affirmation. Eva Hesse dealt with this matter in her writings, in which she indiscriminately wove together the story of her intimate relationship with Tom Doyle, also a sculptor, with the discovery of new material for her work, thus bringing to light her own insecurities within system ruled by male artists. The director of the New Museum, Marcia Tucker, also wrote of her life experience in the book A Short Life of Trouble: Forty Years in the New York Art World, describing her life experience as an indissoluble tool of the art profession. This was along the same lines previously undertaken by Gala Dalí, who revealed herself as an outstanding writer. As Estrella de Diego describes, “If all texts are somewhat autobiographical, a place for negotiating meaning between what is written and what is read, then all life is somewhat fictional. And this is true in the case of Gala, Salvador, and Gala-Salvador Dalí. I still think that autobiography is an extension of fi ction, not the other way round: life is shaped by imagination, more so than by experience.”4

The Culture of this Course (2016)

The Culture of this Course (2016)The inclusion of the works by her father and mother in Cristina Garrido’s exhibition brings to mind other artists who have collaborated directly with their parents. Such is the case of Hanna Wilke, who used her mother as a model; Selma Butter, who did so to speak of illness and death; Vivian Sutter, who works in collaboration with her mother, the expert collage artist Elisabeth Wild; or Dorothy Iannone, who staged exhibitions in dialogue with the works that her mother made and sent her as gifts throughout her life. Although these are all paradigmatic examples, perhaps the greatest exponent of this idea is Anna Maria Maiolino and her legendary photograph alongside her mother and daughter, which readdresses idea of construction and maternity.

The Origin of Forms features many ideas that, like arrows shot in different directions, speak to us of the contextual causes in the formation of artists, of their individual life circumstances and what these mean in terms of the construction of identity, the formation of the creator, and the development of an art career. However, the project also reveals the degree of randomness involved in all of this, and how seemingly trivial facts and events can and do play a decisive role. The concept of luck—that algorithm that is impossible to control yet so powerful when embarking on a career—is also evoked by Sophie Calle when refl ecting, once again, on the role of chance within the fi eld of artistic creation and, more broadly, in existence and human experience.

* * *

Cristina Garrido. Twentieth and twenty-first century. Spanish. White woman. Leo. Born into a family with no artistic background. Her maternal grandfather, a draftsman in a mine in northern Spain, colors in maps as a hobby. Her father, a great admirer of Renoir, encourages her interest in art from a very young age and takes her to world-renowned museums, visiting Paris’ Musée d’Orsay on several occasions. She studies at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, where she specializes in painting and drawing. She spends a year studying in London. Back in Madrid, she soon establishes contact with the most relevant artistic circles of her generation. She travels to different countries thanks to residency programs and grants and, before long, begins to participate in art fairs. She shows her first solo exhibition in a national institution when she is barely thirty years old.

1. As Cristina Garrido herself explains with regards to The Best Job in the World: “Although I collected a wide range of very different testimonies—that is, life stories—this search brought to light some highly dissuasive factors that were shared in all cases with regards to the artists’ decision to abandon the art world: most of them found themselves in a position of economic precariousness, were not encouraged by their families to continue their work, and—even those who had achieved certain visibility in the field for a number of years— did not have the necessary contacts to pursue a long-term art career.” Conversation between Cristina Garrido and Tania Pardo, May 14, 2021.

2. Lucy. R. Lippard, “Foreword,” in Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), pp. 6−11.

3. Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” [1971], in Women, Art, and Power (New York: Harper and Row, 1988), p. 153.

4. Estrella de Diego, “Prólogo,” in Gala Dalí, La vida secreta. Diario íntimo (Madrid: Galaxia Gutenberg, 1998), p. 25.