Joshua Simon

Curator, writer and cultural critic.

‘ Art work and Art job’

Contribution to the book Cristina Garrido. El mejor trabajo del mundo/ Cristina Garrido. The Best Job in the World. Ed. Fundación DIDAC (2022).

“What am I working on? I am working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it.” With this Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), answers reporter Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife (Geena Davis), in a reception at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, in the opening scene of David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986). In this film, a remake of the 1958 film by the same name (directed by Kurt Neumann), Brundle is an inventor who is trying to teleport matter. Although his machine can do so with inorganic things — like Quaife’s stockings — he is unable to transmit living matter. As the movie progresses, things go wrong and as we know, instead of transmitting things, Brundle’s machine transforms him into, well, it is in the film’s title…

All this might sound far away from the professional life of an artist — but the shift from teleportation to metamorphosis we can say, is at its core. What is certain is that Brundle’s response, repeating the question “what am I working on?” should sound familiar to any artist. Usually, the second part of his answer “working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it” is not to be uttered out loud, although we do believe it to a large extent. Something more humble or even selfdeprecating, is the usual answer — something small, temporary, esoteric, might not even see the light of day, etc.

The title of Cristina Garrido’s exhibition at Fundaci.n DIDAC El mejor trabajo del mundo could read as both “the best job in the world,” and “the best work in the world.” As is the case in many languages, in artistic circles, when discussing the actual practice of artmaking, we use freely the word work to describe both the process and the product. When referring to as something we are working on, we are actually describing an ongoing project, a set of restrictions and considerations we are committed to, and to which we have submitted our talents and time — in this sense, we are always working on something that might change the world and human life as we know it. If we were to use the words work and piece, we would see how, the long, ongoing life of artistic work, of a commitment to a process of investigation and production, result sometimes — in failed and successful — attempts to which we can call pieces.

![]() Installation view of the exhibition The Best Job in the World. Fundación DIDAC (Santiago de Compostela, 2021). Image: Roi Alonso.

Installation view of the exhibition The Best Job in the World. Fundación DIDAC (Santiago de Compostela, 2021). Image: Roi Alonso.

In a way, the pieces, the art works, are a by-product of the ongoing work — the labour of being an artist. This labour, as much as it a practice attempting to transmit things, is also a life of transformation. The daily activities of artmaking — whose outcome produces art as a piece — a teleportation of sorts, are in fact a constant struggle to produce oneself as an artist — to get all the mundane procedures and your professional, social and familial ties to support that — to allow for your perpetual metamorphosis.

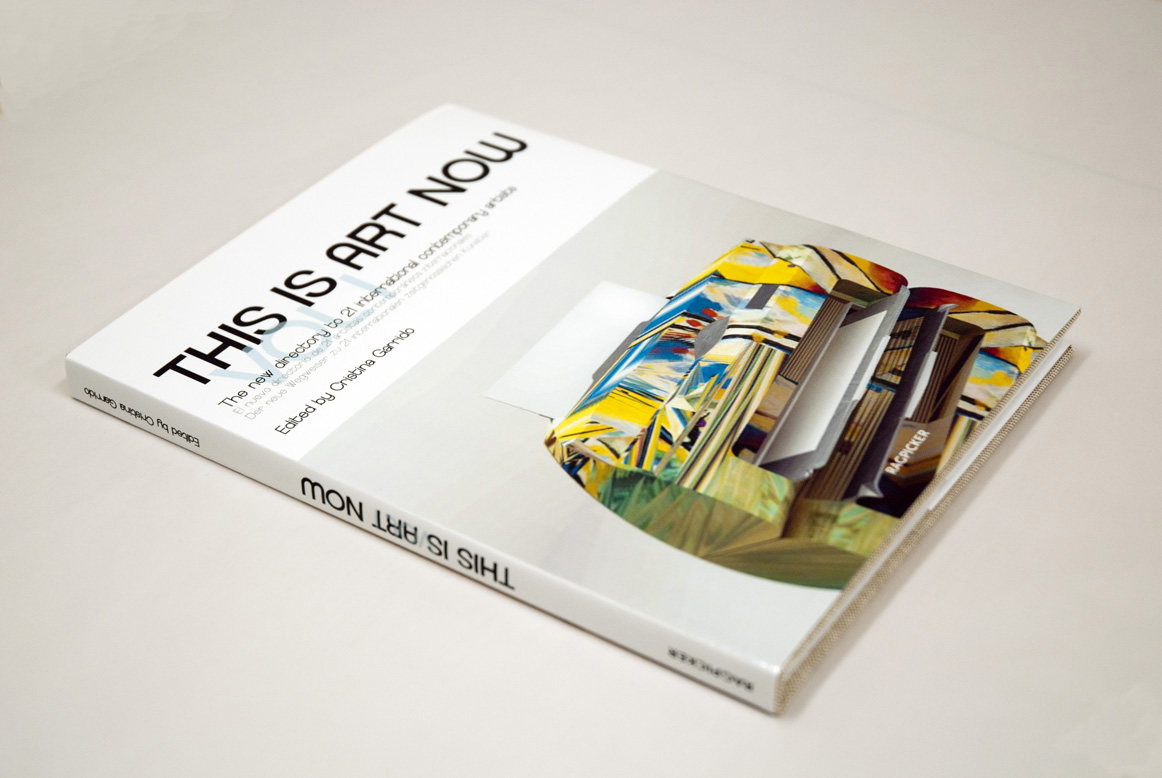

Cristina Garrido has created a unique body of work which is dedicated to the realities of the art world and artistic practices. Taking from art history and institutional critique, Garrido created a series of sincere and humorous works which contemplate and perform the contradictions of artistic work — from its most commercial to its most personal. This is Art Now Vol. 1 (2013), is a book made up of fictional artworks that Garrido created from Components Database of Google SketchUp, positioning them in virtual exhibition spaces. Sensing the speculative qualities of art online almost a decade ago, Garrido sent these renderings to seven art critics and curators, who were invited to interpret the works of each “artist” and to invent biographical details for each of their careers. In her #JWIITMTESDSA? (Just what is it that makes today’s exhibitions so different, so appealing?) installation and research (2015), Garrido focused on the inventory and the look expected from contemporary art online (in gallery and museum sites, blogs and websites like “Contemporary Art Daily”). Making charts of this inventory and composing memes of empty bottles, racks, neon lights, draping fabrics and the likes, Garrido’s work demonstrated how our relation to artistic production has shifted from possibility to probability. This work deployed counter-speculation to provide a genuine look at the speculative nature of contemporary art production. Garrido further developed her interpretations of the

ealities of artistic production and distribution systems, focusing on its display in art fair booths. Garrido’s highly speculative (and funny) film Boothworks (2017) [and parallel photo series “Best Booths,” and subsequent performance Booth Exhibitions are the Institutions of our Time (2020)], uses actual quotes of post-minimalist, conceptual, and land art luminaries as the narration looking back at today and positioning gallery booths in art fairs as a new form of installation art/happening. This future art-documentary which describes the gallery booth at the art fair as the new frontier of artistic practice since the early 2000s. All these projects, although different, are looking at the way art looks in artbooks, online, in fairs — or to put it differently — they look at how things perform as art.

![]() This Is Art Now Vol. 1, 2013

This Is Art Now Vol. 1, 2013

Her moving film and book The (Invisible) Art of Documenting Art, 2019, is dedicated to eight prominent art photographers who are documenting installations for galleries and institutions for catalogs and PR mainly in Europe. This project focuses its attention on art photographers who document art exhibitions, and in that sense make them public much more than other practitioners involved in the process (just think of Alfred Steiglitz’s photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain). The unseen practice of documentary photographers of contemporary art, taking installation views of exhibitions, is part and parcel of how we experience art. Complementing this project, is Garrido’s The Copyist (2018-2019), in which she invited Román Blázquez, a renowned authorized copyist of the Prado Museum, to work on a regular basis in the halls of the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo contemporary art center. What resulted were oil on canvas paintings depicting the exhibition space which were gradually hung on the walls, becoming part of the exhibition itself. These projects look at the who is making things perform as art.

Garrido’s work has focused on the innerworkings of contemporary art systems while addressing their structural inequalities and discrepancies. She has created a variety of online interventions, videos, books, performances, installations and photographic displays, that used the tutorial, the documentary, the testimonial, the taxonomical, the classroom, the advertisement brochure, and other formats of mediating art, to address the production and circulation systems of art, with their economies of attention and hype as well as their realities of labour and commodification. In El mejor trabajo del mundo she looks both at how things perform as art and who is making them perform as art — it focuses on the two elements of mapping the field and enacting its blind spots.

El mejor trabajo del mundo [The Best Job in the World] looks at yet another unseen but well-established part of the art world — artists who have stopped making art. Life situations, circumstances but also conscious decisions can lead artists to stop making art. We know that Marcel Duchamp famously resigned from making art and retired to chess mastery. He was still involved with the re-issue of his readymades with Milanese gallerist Arturo Schwarz in 1964, and made secretly Étant donnés (1946-1966). This leads to the question, when is the moment one ceases to be an artist? In one’s lifetime it might be in relation to their last artwork, or the moment they relinquish the title of artist — but then again, dead-artists, even though they stopped making work (sometimes centuries ago) are still artists. And so, when they die, these artists who decided not to make art again andm not to be considered artists, might be yet again regarded as artists — because art history or the art market, friends or others — would see them as such.

And so, looking at this well-established, but little documented phenomenon, Garrido’s research on artists from different generations and contexts who have voluntarily or involuntarily stopped practicing and exhibiting their work, puts the viewer in a position where she is both consumed by the work and reflecting on the conditions it portrays. The viewer is therefore encouraged to perceive her own self within the different contemporary art economies of viewing. In this case, how an artist becomes an artist not by their sheer willpower and talent, but by the viewer who validates them as such. The viewer becomes a transmission device for someone to metamorph into an artist.

Garrido is deploying a group exhibition of no-longer-artists. A kind of Art-brut in reverse — where all the participants are not non-artists, and yet, their distance from artistic practices today is what qualifies them to take part in the exhibition.

In her work, Garrido explores what contemporary art is made up of. Her conceptual gestures, in the form of art pieces, reflect on the fundamentals of contemporary art and the input of the mediators in the center of it. We see in her work how art appears and who are some of the invisible agents that allow it to exist. Training to become an artist, the setting for learning and making that makes the art school, is where the new is constantly being explored. Unlike any other field, as part of their practice, art students (fine arts, architecture, and curatorial studies students), go through a critic, which expands their ability to evaluate their own work outside of themselves. This is distinctive to the field and takes place within a setting that has the potential of being open and unscripted. From its silences to the occasional “hijacking the conversation,” the crits are an event that marks itself uncharted. Summoning the new here, takes place collectively, in the presence of works, students and faculty. Together, they are teleporting assignments and incomplete assignments, into art-works.

![]() Boothworks, 2017

Boothworks, 2017

After the 18th century, philosophy abstracted all categories of judgment in the service of all practical fields. An engineer or doctor did not need to ask herself anymore whether what she is doing is engineering or medicine. As so, while in other fields this has been forgotten, in the arts we are still required to ask what is art — what is the field itself that we are practicing in. In this sense, every artist is also a philosopher of art. Even the powerful history of philosophy, pragmatism and instrumentalization, has been unsuccessful in making the arts forget this core question which reflects on the function and meaning of art making and of living with art. Up until a few centuries ago, engineers, doctors and economists were demanded as well to ask themselves — as part of their practice — what makes their practice and field, what is its meaning and function. Those questions required each practitioner to also be a philosopher of the practice. As these questions are still vibrant to this day as part of artistic practice, the arts became the place which holds them at its core. When it comes to artistic practice and training, the way art schools do that is by inviting the students themselves to provide the scale and perspective on their own practice. No one is telling an art student what artworks to make and how. They bring the work, and then the conversation begins. Few if any are the contemporary art schools which would tell their students “this is how we make art here.” And so, the art school is also a site for evaluating a crisis of perspective authority — should this be treated as a complete work of art, as something on the way of becoming an artwork?

Through their workshops, classes, masterclasses and their crits, art schools are meant to teach you how to make art, to create pieces. But through socialisation, modeling, conversation (and now some courses on self-marketing mainly), you are learning to become an artist — to contain and sustain this way of working, this ongoing research and labour. All this is done in the service of exploring the new.

Exploring the new has been the hallmark of artistic practices since modernity’s inception. It was the practice of teleportation by metamorphosis — transmitting things by transforming the people involved in the practice (artists and viewers alike). Ken Lum’s 1989 Melly Shum HATES Her Job, is a billboard showing a young woman wearing glasses turning her head to the camera in an office setting. The work was installed facing the Witte de With street in Rotterdam, as part of Lum’s solo exhibition there in 1990. Back then the art space which invited Lum to exhibit, was called Witte de With Art Institute. Since January 2021 it is called Kunstinstituut Melly Rotterdam, after the woman depicted in Lum’s poster. This meme-before-there-were-memes, in the spirit of Vancouver post-conceptual photography of the time, can help us think of El mejor trabajo del mundo. By its setting and framing, we can see that Melly’s job is somewhat administrative and bureaucratic, nothing exciting. This is not the place where she can express her passions and talents. We get it why she hates her job. By naming the art space after the protagonist of the piece, this work became an icon, or even a monument, to the difference between how people experience their jobs (unfulfilled, frustrated, resentful), and how artists are supposed to view their practice (never simply as a job). But what happens when an artist hates her job as an artist? What does it mean that the work of making art — where one’s own passions and talents are supposed to be expressed — is something you no longer like?

What am I working on? I am working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it. I stopped making art.

Curator, writer and cultural critic.

‘ Art work and Art job’

Contribution to the book Cristina Garrido. El mejor trabajo del mundo/ Cristina Garrido. The Best Job in the World. Ed. Fundación DIDAC (2022).

“What am I working on? I am working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it.” With this Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), answers reporter Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife (Geena Davis), in a reception at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, in the opening scene of David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986). In this film, a remake of the 1958 film by the same name (directed by Kurt Neumann), Brundle is an inventor who is trying to teleport matter. Although his machine can do so with inorganic things — like Quaife’s stockings — he is unable to transmit living matter. As the movie progresses, things go wrong and as we know, instead of transmitting things, Brundle’s machine transforms him into, well, it is in the film’s title…

All this might sound far away from the professional life of an artist — but the shift from teleportation to metamorphosis we can say, is at its core. What is certain is that Brundle’s response, repeating the question “what am I working on?” should sound familiar to any artist. Usually, the second part of his answer “working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it” is not to be uttered out loud, although we do believe it to a large extent. Something more humble or even selfdeprecating, is the usual answer — something small, temporary, esoteric, might not even see the light of day, etc.

The title of Cristina Garrido’s exhibition at Fundaci.n DIDAC El mejor trabajo del mundo could read as both “the best job in the world,” and “the best work in the world.” As is the case in many languages, in artistic circles, when discussing the actual practice of artmaking, we use freely the word work to describe both the process and the product. When referring to as something we are working on, we are actually describing an ongoing project, a set of restrictions and considerations we are committed to, and to which we have submitted our talents and time — in this sense, we are always working on something that might change the world and human life as we know it. If we were to use the words work and piece, we would see how, the long, ongoing life of artistic work, of a commitment to a process of investigation and production, result sometimes — in failed and successful — attempts to which we can call pieces.

Installation view of the exhibition The Best Job in the World. Fundación DIDAC (Santiago de Compostela, 2021). Image: Roi Alonso.

Installation view of the exhibition The Best Job in the World. Fundación DIDAC (Santiago de Compostela, 2021). Image: Roi Alonso.In a way, the pieces, the art works, are a by-product of the ongoing work — the labour of being an artist. This labour, as much as it a practice attempting to transmit things, is also a life of transformation. The daily activities of artmaking — whose outcome produces art as a piece — a teleportation of sorts, are in fact a constant struggle to produce oneself as an artist — to get all the mundane procedures and your professional, social and familial ties to support that — to allow for your perpetual metamorphosis.

Cristina Garrido has created a unique body of work which is dedicated to the realities of the art world and artistic practices. Taking from art history and institutional critique, Garrido created a series of sincere and humorous works which contemplate and perform the contradictions of artistic work — from its most commercial to its most personal. This is Art Now Vol. 1 (2013), is a book made up of fictional artworks that Garrido created from Components Database of Google SketchUp, positioning them in virtual exhibition spaces. Sensing the speculative qualities of art online almost a decade ago, Garrido sent these renderings to seven art critics and curators, who were invited to interpret the works of each “artist” and to invent biographical details for each of their careers. In her #JWIITMTESDSA? (Just what is it that makes today’s exhibitions so different, so appealing?) installation and research (2015), Garrido focused on the inventory and the look expected from contemporary art online (in gallery and museum sites, blogs and websites like “Contemporary Art Daily”). Making charts of this inventory and composing memes of empty bottles, racks, neon lights, draping fabrics and the likes, Garrido’s work demonstrated how our relation to artistic production has shifted from possibility to probability. This work deployed counter-speculation to provide a genuine look at the speculative nature of contemporary art production. Garrido further developed her interpretations of the

ealities of artistic production and distribution systems, focusing on its display in art fair booths. Garrido’s highly speculative (and funny) film Boothworks (2017) [and parallel photo series “Best Booths,” and subsequent performance Booth Exhibitions are the Institutions of our Time (2020)], uses actual quotes of post-minimalist, conceptual, and land art luminaries as the narration looking back at today and positioning gallery booths in art fairs as a new form of installation art/happening. This future art-documentary which describes the gallery booth at the art fair as the new frontier of artistic practice since the early 2000s. All these projects, although different, are looking at the way art looks in artbooks, online, in fairs — or to put it differently — they look at how things perform as art.

This Is Art Now Vol. 1, 2013

This Is Art Now Vol. 1, 2013Her moving film and book The (Invisible) Art of Documenting Art, 2019, is dedicated to eight prominent art photographers who are documenting installations for galleries and institutions for catalogs and PR mainly in Europe. This project focuses its attention on art photographers who document art exhibitions, and in that sense make them public much more than other practitioners involved in the process (just think of Alfred Steiglitz’s photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain). The unseen practice of documentary photographers of contemporary art, taking installation views of exhibitions, is part and parcel of how we experience art. Complementing this project, is Garrido’s The Copyist (2018-2019), in which she invited Román Blázquez, a renowned authorized copyist of the Prado Museum, to work on a regular basis in the halls of the Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo contemporary art center. What resulted were oil on canvas paintings depicting the exhibition space which were gradually hung on the walls, becoming part of the exhibition itself. These projects look at the who is making things perform as art.

Garrido’s work has focused on the innerworkings of contemporary art systems while addressing their structural inequalities and discrepancies. She has created a variety of online interventions, videos, books, performances, installations and photographic displays, that used the tutorial, the documentary, the testimonial, the taxonomical, the classroom, the advertisement brochure, and other formats of mediating art, to address the production and circulation systems of art, with their economies of attention and hype as well as their realities of labour and commodification. In El mejor trabajo del mundo she looks both at how things perform as art and who is making them perform as art — it focuses on the two elements of mapping the field and enacting its blind spots.

El mejor trabajo del mundo [The Best Job in the World] looks at yet another unseen but well-established part of the art world — artists who have stopped making art. Life situations, circumstances but also conscious decisions can lead artists to stop making art. We know that Marcel Duchamp famously resigned from making art and retired to chess mastery. He was still involved with the re-issue of his readymades with Milanese gallerist Arturo Schwarz in 1964, and made secretly Étant donnés (1946-1966). This leads to the question, when is the moment one ceases to be an artist? In one’s lifetime it might be in relation to their last artwork, or the moment they relinquish the title of artist — but then again, dead-artists, even though they stopped making work (sometimes centuries ago) are still artists. And so, when they die, these artists who decided not to make art again andm not to be considered artists, might be yet again regarded as artists — because art history or the art market, friends or others — would see them as such.

And so, looking at this well-established, but little documented phenomenon, Garrido’s research on artists from different generations and contexts who have voluntarily or involuntarily stopped practicing and exhibiting their work, puts the viewer in a position where she is both consumed by the work and reflecting on the conditions it portrays. The viewer is therefore encouraged to perceive her own self within the different contemporary art economies of viewing. In this case, how an artist becomes an artist not by their sheer willpower and talent, but by the viewer who validates them as such. The viewer becomes a transmission device for someone to metamorph into an artist.

Garrido is deploying a group exhibition of no-longer-artists. A kind of Art-brut in reverse — where all the participants are not non-artists, and yet, their distance from artistic practices today is what qualifies them to take part in the exhibition.

In her work, Garrido explores what contemporary art is made up of. Her conceptual gestures, in the form of art pieces, reflect on the fundamentals of contemporary art and the input of the mediators in the center of it. We see in her work how art appears and who are some of the invisible agents that allow it to exist. Training to become an artist, the setting for learning and making that makes the art school, is where the new is constantly being explored. Unlike any other field, as part of their practice, art students (fine arts, architecture, and curatorial studies students), go through a critic, which expands their ability to evaluate their own work outside of themselves. This is distinctive to the field and takes place within a setting that has the potential of being open and unscripted. From its silences to the occasional “hijacking the conversation,” the crits are an event that marks itself uncharted. Summoning the new here, takes place collectively, in the presence of works, students and faculty. Together, they are teleporting assignments and incomplete assignments, into art-works.

Boothworks, 2017

Boothworks, 2017After the 18th century, philosophy abstracted all categories of judgment in the service of all practical fields. An engineer or doctor did not need to ask herself anymore whether what she is doing is engineering or medicine. As so, while in other fields this has been forgotten, in the arts we are still required to ask what is art — what is the field itself that we are practicing in. In this sense, every artist is also a philosopher of art. Even the powerful history of philosophy, pragmatism and instrumentalization, has been unsuccessful in making the arts forget this core question which reflects on the function and meaning of art making and of living with art. Up until a few centuries ago, engineers, doctors and economists were demanded as well to ask themselves — as part of their practice — what makes their practice and field, what is its meaning and function. Those questions required each practitioner to also be a philosopher of the practice. As these questions are still vibrant to this day as part of artistic practice, the arts became the place which holds them at its core. When it comes to artistic practice and training, the way art schools do that is by inviting the students themselves to provide the scale and perspective on their own practice. No one is telling an art student what artworks to make and how. They bring the work, and then the conversation begins. Few if any are the contemporary art schools which would tell their students “this is how we make art here.” And so, the art school is also a site for evaluating a crisis of perspective authority — should this be treated as a complete work of art, as something on the way of becoming an artwork?

Through their workshops, classes, masterclasses and their crits, art schools are meant to teach you how to make art, to create pieces. But through socialisation, modeling, conversation (and now some courses on self-marketing mainly), you are learning to become an artist — to contain and sustain this way of working, this ongoing research and labour. All this is done in the service of exploring the new.

Exploring the new has been the hallmark of artistic practices since modernity’s inception. It was the practice of teleportation by metamorphosis — transmitting things by transforming the people involved in the practice (artists and viewers alike). Ken Lum’s 1989 Melly Shum HATES Her Job, is a billboard showing a young woman wearing glasses turning her head to the camera in an office setting. The work was installed facing the Witte de With street in Rotterdam, as part of Lum’s solo exhibition there in 1990. Back then the art space which invited Lum to exhibit, was called Witte de With Art Institute. Since January 2021 it is called Kunstinstituut Melly Rotterdam, after the woman depicted in Lum’s poster. This meme-before-there-were-memes, in the spirit of Vancouver post-conceptual photography of the time, can help us think of El mejor trabajo del mundo. By its setting and framing, we can see that Melly’s job is somewhat administrative and bureaucratic, nothing exciting. This is not the place where she can express her passions and talents. We get it why she hates her job. By naming the art space after the protagonist of the piece, this work became an icon, or even a monument, to the difference between how people experience their jobs (unfulfilled, frustrated, resentful), and how artists are supposed to view their practice (never simply as a job). But what happens when an artist hates her job as an artist? What does it mean that the work of making art — where one’s own passions and talents are supposed to be expressed — is something you no longer like?

What am I working on? I am working on something that will change the world and human life as we know it. I stopped making art.